ON Christmas Eve, 1956, a 15-year-old boy heads due south on a five-hour Greyhound Bus journey from his home in Hibbing, Minnesota.

Arriving in the state capital, Saint Paul, he meets up with two summer camp friends and they go to a shop on Fort Road called Terlinde Music.

Styling themselves as The Jokers, the fledgling trio record a rowdy, rudimentary 36-second rendition of R&B party hit Let The Good Times Roll and a handful of other covers.

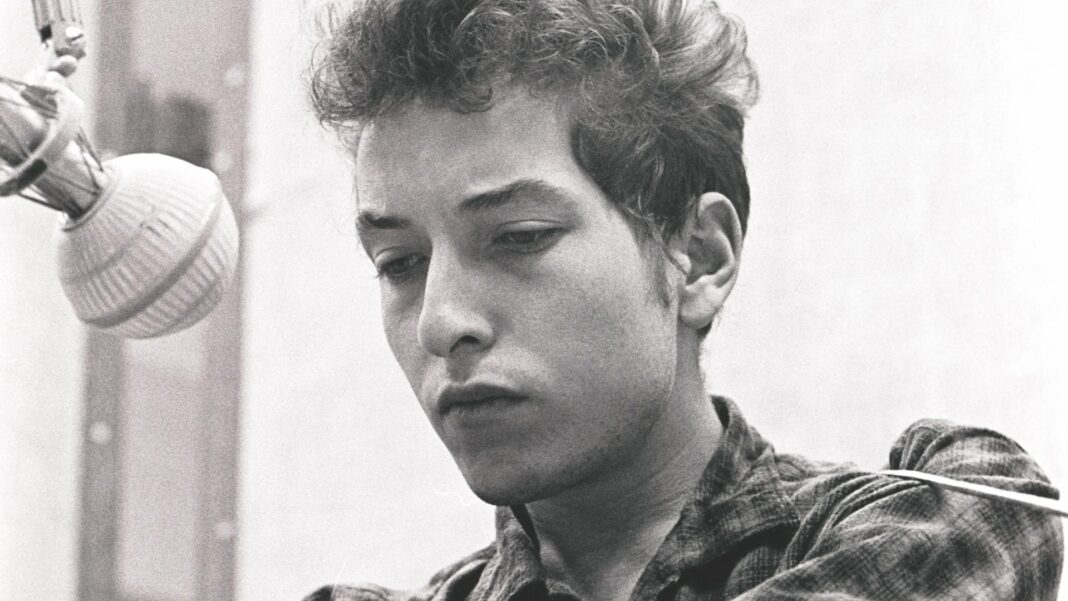

The boy, with his chubby cheeks and hint of a rock and roller’s quiff, leads the way on vocals and piano.

Already enthralled by popular sounds of the day from Elvis Presley to Little Richard and the rest, he is now in proud possession of a DIY acetate — his first precious recording.

His name is Robert Allen Zimmerman, Bobby to his family and friends.

LEGEND GONE

Bob Dylan bandmate dies aged 83 after blues musician backed star to go electric

DULCIE PEARCE

Bob Dylan’s story is brought to life in star-studded A Complete Unknown

Less than seven years later, on October 26, 1963, as Bob Dylan, he takes to the stage in the manner of his folk hero Woody Guthrie, now adopting an altogether more lean and hungry look.

Acoustic guitar and harmonica are his only props as he holds an audience at New York City’s prestigious Carnegie Hall in the palms of his hands.

He performs his rallying cries that resonate to this day — Blowin’ In The Wind, The Times They Are A-Changin’, A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.

He calls out the perpetrators of race-motivated killings with The Lonesome Death Of Hattie Carroll and Only A Pawn In Their Game.

He dwells on matters of the heart by singing Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right and Boots Of Spanish Leather.

His 1956 schoolboy shindig and the Carnegie Hall concert, presented in full for the first time, bookend the latest instalment in Dylan’s endlessly captivating Bootleg Series.

Titled Through The Open Window, it showcases an artist in a hurry as he sets out on his epic career.

“I did everything fast,” he wrote in his memoir, Chronicles Vol.1, about his rapid transformation. “Thought fast, ate fast, talked fast and walked fast. I even sang my songs fast.”

But, as he continued: “I needed to slow my mind down if I was going to be a composer with anything to say.”

Among the myriad ways he achieved his stated aim, and then some, was by heading to the quiet surroundings of New York Public Library and avidly scouring newspapers on microfilm from the mid-1800s such as the Chicago Tribune and Memphis Daily Eagle, “intrigued by the language and the rhetoric of the times”.

He’d fallen under the spell of country music’s first superstar Hank Williams — “the sound of his voice went through me like an electric rod”.

Dylan affirmed that without hearing the “raw intensity” of songs by German anti-fascist poet-playwright Kurt Weill, most notably Pirate Jenny, he might not have written songs like The Lonesome Death Of Hattie Carroll.

Then there was Mississippi Delta bluesman Robert Johnson, who Dylan likened to “the scorched earth”. “There’s nothing clownish about him or his lyrics,” he said. “I wanted to be like that, too.”

‘Did everything fast’

We’ll hear more later about the man considered to be his primary early influence, Woody Guthrie, the “Dust Bowl Balladeer” who wielded a guitar emblazoned with the slogan “This machine kills fascists”.

And about leading Greenwich Village folkie Dave Van Ronk, known as the “Mayor Of MacDougal Street”, who had Dylan’s back from the moment he first saw him sing.

On two occasions in recent years, I’ve had the privilege of talking to Joan Baez, the unofficial “Queen” to Dylan’s “King” of the American folk scene in the early Sixties.

She championed him as he made his way, frequently bringing him on stage, their duets on his compositions like With God On Our Side revealing rare chemistry.

They also became lovers as Bob’s relationship with Suze Rotolo, the girl on the cover of the Freewheelin’ album, crumbled.

“He was a phenomenon,” Baez told me in typically forthright fashion. “I guess somebody said, ‘There’s this guy you gotta hear, he’s writing these incredible songs.’

“And he was. His talent was so constant that I was in awe.”

A leading figure in the civil rights movement, who marched with Martin Luther King, Baez added: “It was a piece of good luck that his music came along when it did. The songs said the things I wanted to say.”

But she finished that reflection by saying, tellingly: “And then he moved on.”

For Dylan, now 84, has forever been a restless soul, “moving on” to numerous incarnations — rock star, country singer, Born Again evangelist, Sinatra-style crooner, old-time bluesman, you name it.

In the closing paragraph of Chronicles, he admitted: “The folk music scene had been like a paradise that I had to leave, like Adam had to leave the garden.”

But it is that initial whirlwind period, 1956 to 1963, centred on bohemian Greenwich Village and the coffee shops where young performers got their breaks which forms Volume 18 of the Bootleg Series.

Through The Open Window is available in various formats including an eight-CD, 139-track version, and has been painstakingly pieced together by co-producers Sean Wilentz and Steve Berkowitz.

And it is from Wilentz, professor of American history at Princeton University and author of the liner notes accompanying this labour of love, that I have gleaned illuminating insights.

I can’t think of too many modern artists of his stature, if any, who developed that rapidly

Sean Wilentz

He begins with the arc of Dylan’s development, first as a performer, then as a songwriter, during his early years.

Wilentz says: “He came to Greenwich Village in 1961 with infinite ambition and mediocre skills. By the end of that year, he had learned how to enter a song, make it his own, and put it over, brilliantly.

“By the end of 1962, he had written songs that became immortal, above all Blowin’ In The Wind and A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.

“By the time of the Carnegie Hall concert in 1963, the capstone to Through The Open Window, his songwriting had reached the level we can recognise, that would eventually lead to the Nobel Prize.

“And his performance style, for the thousands in that hall, was mesmeric. I can’t think of too many modern artists of his stature, if any, who developed that rapidly.”

One of the show’s striking aspects is the lively, often comical, between-song banter. (Yes, Dylan did talk effusively to his audiences back then. Not so much these days.)

In order to assemble Through The Open Window, Wilentz and Berkowitz had “more than 100 hours of material to draw on, maybe two or even three hundred”.

Their chief aim was to find a way to best illuminate “Bob Dylan’s development, mainly in Greenwich Village, as a performer and songwriter”.

But, adds Wilentz: “Several factors came into play — historical significance, rarity, immediacy and, of course, quality of performance.

‘Good taste in R&B’

“We hope, above all, that the collection succeeds at capturing the many overlapping levels — personal, artistic, political and more.”

Though noting Dylan’s inspirations, Woody, Elvis and the rest, Wilentz draws my attention to “a bit of free verse” written by Bob in 1962 called My Life In A Stolen Moment, which suggests nothing was off limits.

“Open up yer eyes an’ ears an’ yer influenced/an’ there’s nothing you can do about it.”

This is our cue to take a deep dive into the mix of unheard home recordings, coffeehouse and nightclub shows as well as studio outtakes from Dylan’s first three albums for Columbia Records — his self-titled debut, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan and The Times They Are A-Changin’.

Of the first track, that primitive take on Let The Good Times Roll, Wilentz says: “Dylan and the other two were obviously enthusiastic, and they had good taste in doo-wop and R&B.

“But if you listen closely, you can hear Dylan, on piano, calling things to order and pushing things along, the catalyst, the guy we know from other accounts who was willing to take more risks onstage.”

I ask Wilentz what he considers the most significant previously unreleased discoveries and he replies: “Most obviously Liverpool Gal from 1963, as it’s a song even the most obsessive Dylan aficionados have known existed but had never heard.

“He only recorded it once, at a friend’s party, and it’s stayed locked away on that tape until now.

Dylan was producing so much strong material that some of it was inevitably laid aside

Sean Wilentz

“While not Dylan at his peak, it’s a fine song. It’s significant lyrically, not least as testimony to his stay in London at the end of 1962 and the start of 1963. That stay had a profound effect on his songwriting, and one gets a glimpse of it here.”

Also included is near mythical Dylan song The Ballad Of The Gliding Swan, which he performed as “Bobby” in BBC drama Madhouse On Castle Street during his trip to Britain.

The only copy of the play set in a boarding house was junked by the Beeb in 1968 but this 63-second audio fragment survives.

Of even earlier recordings, Wilentz says: “I’m drawn to Ramblin’ Round.

“Although known (in his own words) as a Woody Guthrie jukebox, Dylan has never released a recording of himself performing a Guthrie song.

“Here he is, in an outtake from his first studio album, handling a Guthrie classic, and with a depth of feeling that shows why his earliest admirers found him so compelling.”

Wilentz considers other treasures: “There’s an entire 20-minute live set from Gerdes Folk City from April, 1962, concluding with Dylan’s first public performance of Blowin’ In The Wind.

“Then there are two tracks of singular historic importance, the first known recordings, both in informal settings, of two masterpieces, The Lonesome Death Of Hattie Carroll and The Times They Are A-Changin’.”

If these versions shed fresh light on classics, let’s not forget the great Dylan songs that didn’t make it on to his albums, so great was the speed he was moving.

Does Wilentz find it staggering that songs like Let Me Die In My Footsteps and Lay Down Your Weary Tune were discarded?

“Yes and no,” he answers. “Yes, because these are powerful songs that were left largely unknown for years.

“No, because Dylan was producing so much strong material that some of it was inevitably laid aside.

‘Literary genius’

“Sometimes intervening factors kicked in. Take the four songs that, for business and censorship reasons, got cut from Freewheelin’ and replaced with four others.

“The album was actually better in its altered form, including songs like Girl From The North Country.

“But that’s how Let Me Die In My Footsteps was lost, along with a lesser-known song I love that we’re happy to include, Gamblin’ Willie’s Dead Man’s Hand, as well as an amazing performance of Rocks And Gravel.”

So, we’ve heard about songs but who were the key figures surrounding Dylan during his formative years?

Wilentz says: “Among the folk singers, Van Ronk most of all, and Mike Seeger, about whom he writes with a kind of awe in Chronicles.

“There was the crowd around Woody Guthrie, including Pete Seeger (‘Mike Seeger’s older brother,’ he calls him at one point) and Ramblin’ Jack Elliott.”

He singles out producer John Hammond, “for signing him to Columbia Records and affirming his talent.

“But most important of all there was Suze Rotolo, who was a whole lot more, to Dylan and the rest of the world, than the girl on the cover of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan.”

Finally, I ask Wilentz why the singer felt uncomfortable at being labelled king of the folk movement, “the voice of a generation” if you like.

“People misread Dylan from all sides,” he argues. “Never a protest singer in the mould of Guthrie or Seeger, even though he worshipped Guthrie and admired the left-wing old guard by the time he turned up.

“But Dylan wasn’t one of them, though he sympathised, in a humane way, with victims of injustice.”

Dylan’s work springs from a matrix that is emotional, filtered through his literary genius

Sean Wilentz

Wilentz believes the recent biopic A Complete Unknown, with Timothee Chalamet making a decent fist of portraying the young Dylan, “is a little misleading”.

He says: “It wasn’t Dylan’s ‘going electric’ that pissed off the old guard and their younger equivalent as much as his moving beyond left-wing political pieties.

“Hence the song My Back Pages, from 1964: ‘Ah but I was so much older then/I’m younger than that now.’”

Wilentz concludes: “Dylan’s work springs from a matrix that is emotional, filtered through his literary genius.

“It was impossible for someone like him, living through those two years (1962-63), not to respond to the politics in an artistic way.

“How, if you were Bob Dylan, could you not respond to the civil rights struggle, the killing of Medgar Evers (Only A Pawn In Their Game) or Hattie Carroll, as well as the spectre of nuclear annihilation?

“Dylan had a lot to say, but he was never going to be the voice of anyone but himself.”

Maybe he’d already explained himself on Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright:

“When your rooster crows at the break of dawn

STRICTLY NEWBIES

All the stars in line to replace Tess and Claudia on Strictly

TUM HELP

The 30g diet hack that ‘PREVENTS deadly bowel cancer’… as cases surge in under-50s

Look out your window and I’ll be gone.”

BOB DYLAN

Through The Open Window

The Bootleg Series Vol.18